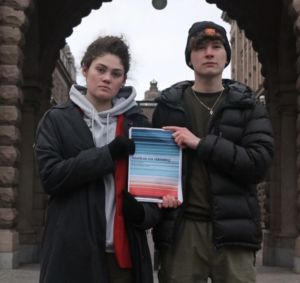

Listeners to the Irish In Sweden podcast will be aware that young Swedish-Irishman Anton Foley is suing the Swedish state over their inaction in relation to the climate emergency, and the District Court in Nacka has recently ruled that the state may have a case to answer.

The matter – known as “Auroramålet” (the Aurora case) – came before the court on March 21, and the court gave the state three months to answer the suit from Anton & others.

That answer will decided the next steps in the case, which Anton has said could go all the way to the Supreme Court, or indeed the European Court Of Human Rights – and needless to say, this website will be following developments as they happen.

Below is a transcript of Anton’s recent conversation with Philip, which appeared on the podcast.

Philip: Anton Foley, tell me why you decided to sue the Swedish government on behalf of the environment.

Anton: Yeah, so obviously we’re in a multifaceted climate and ecological emergency and government action is still moving in the wrong direction. Emissions are increasing, and at the same time, we’re hearing these promises and fancy words about how we’re heading

in the right direction when all the numbers and all the science is saying the exact opposite. We’re heading in the wrong direction. And when you’re in this type of situation, you take every every tool at your disposal in order to combat this.

So that includes protests, that includes civil disobedience, and that includes legal action. And taking the government to court is an important part of a democratic justice system.

Philip: Was it the 25th of November last year that it sort of became official, the papers were

presented to the court? What’s the basis of the action that you’re taking against the government?

Anton: The basis of the action legally is the ECHR, so the European Convention on Human Rights, which binds most countries in Europe, and it’s encoded into Swedish law.

And basically, our argument is that the climate crisis is violating and is threatening to violate the human rights of young people in Sweden.

We will face consequences from the climate crisis that threaten our right to life, our right to health, to a livable environment, basically.

So it’s a fairly simple argumentation that the Swedish government, by not taking sufficient action to reduce its emissions, is failing to do its fair share of the global action needed, and therefore is in violation of this responsibility to protect our human rights.

Philip: It’s not something one does lightly, right? So when you arrive and bang on the door of the court and say, right, I’m going to sue the government, did you have to get legal advice from qualified lawyers or is this something that sometimes citizens can do these things themselves? Which path did you decide to go down?

Anton: Yeah, well, obviously we have legal professionals involved. It’s a challenging court case. It’s not something that’s been done in Sweden before. The precedent has been set in various countries in Europe and around the world, but it’s still very new, very cutting edge.

So there’s a lot of creativity that the lawyers need to employ in order to figure out how to go about this. So we’ve had a fairly sizable team of lawyers involved in advising and producing the actual lawsuit, and actually a lot of it’s been done by law students and young lawyers who are working pro bono on this as part of a wider environmental movement with young people deciding to take action.

Philip: That was going to be the next question, but you kind of answered it there because legal action is often extremely expensive and the higher up the court system you go, I can see you go, ”Jesus …”, I know, you know. How do you deal with that? Because I’d imagine that a certain amount of it can be done by legal students pro bono, but at some point somebody is going to have their hand out and say, look, you guys got to pay me if I’m going to take this before a judge.

Anton: So our lead lawyer is obviously paid. I mean, you can’t really get anything done otherwise. And I’m actually in charge of funding for the case. So that has been one of the major challenges in order to figure out how much money do we need and then how do we procure these fairly sizable amounts of funds. And a lot of it’s been coming through crowdfunding, which has been immensely successful.

When we’ve produced media attention, we’ve generated large sums of money, actually. And we’re looking at every way we can find money is being explored.

Philip: Were you surprised by how much legal action costs? Because sometimes you go, okay, well, I’ll do that and it’ll cost 20, 30, 50,000. Definitely a bit of a shock. How much money do you think between your thumb and your pointing finger, as we say in Swedish,

how much money would you actually need if you were going to be successful with this kind of legal action?

Anton: Well, you need to separate two separate categories here. First, we’ve got our direct costs and that’s how much do we need to pay our lawyers, which is the majority of our expenses. We have very few other expenses other than legal costs.

And the other part is that if we lose and we become liable for our position costs – that can really run away from you, and it’s also really difficult for us to predict. Obviously the Swedish government and the Swedish state has significantly larger resources than we do, so they might be able to pull in a really expensive law firm and then those costs can really get away from us, but it’s a few hundred thousand euros is sort of what we’re talking about for direct costs, a couple hundred thousand euros. And then how much we might end up being liable to pay for is hard to know, but the same amount and upwards. It’s a presumption.

Philip: It’s not going to cost less than your own legal costs anyway.

Anton: Presumably not.

Philip: Your name, and this is the reason we’re talking, is because your name is the one that’s on the legal papers. It’s Anton Foley and others who are taking on the Swedish government. Does that mean that you personally could end up being liable for these hundreds of thousands, if not millions of euros, in legal costs should this not turn out in your favor?

Anton: Basically yes, but through a contract with Aurora as the organization, which is the organization I’m a part of and the organization who has prepared this case and is bringing the case. We have a contract there, which means that it’s like…

Philip: They take on the liability?

Anton: Yes, exactly. So we as an organization will cover that and take on that liability. So we’re working as an organization now, and like I said, I’m in charge of funding. So a large part of the funding work is trying to find money to be able to be insured against that risk.

Philip: I often find when you talk to lawyers, like they’re the most positive people in the world, and then you pay them and they go, oh no, that was never going to work.

What do they see as your chances of success? Is this a toss of a coin? Is it 50-50? Is it 80% chance you’re going to win? Is it 10%?

Anton: That’s the kind of question that everybody wants to know. We want to put a percentage on it. And it’s really, really difficult to predict because like I said, this is groundbreaking. It’s the first time it’s being done. So there’s no real precedent to run by. We do see that environmental cases or climate action lawsuits like this have been really effective and have won, have been won in various countries around the world, most notably maybe

in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, recently in Europe, which is notable because the basis for those cases, largely the ECHR just as it is for us. So in countries with similar legal systems with the same legal papers sort of being the ground for our claims, cases have been won. But we are doing things slightly differently from them. We are trying new things. We are experimenting. And obviously, each country will have its own unique system. And you never know what judges you’re going to get or how the courts will respond.

So it’s very, very difficult to predict.

Philip: It’s always a risky business because the other thing is one judge might decide in your favor, another might decide against, and they’re very learned people. They know what they’re dealing with. The basis of that case – if I want to sue somebody, usually I have to prove that I personally have been injured by this. Will you be asked to make that case in court, do you think? Or is this just something that’s going to be worked out behind closed doors between your lawyers, their lawyers, and the Swedish legal system?

Anton: That’s actually a really interesting question. I don’t know how much of the disagreement will be worked out behind closed doors and how much will actually end up in a court. Like I’m not a law student, I haven’t studied law, so I’m new to all of this. And it’s really exciting figuring out how this type of thing happens in practice.

Our case is a bit different. We’re not working on the case that we’ve already suffered damages, but it’s based on the risk of those human rights being violated in the future. And that’s why all of the claimants were 600 young people, who are sort of claimants against

the state here. Everybody’s young, because, yeah, like the climate crisis is already hitting today, but it will escalate into the future. And it’s really interesting. Like, we haven’t received a response from the state yet. First the court needs to make a decision on whether they’ll hear the case or not. After that, the state will come with a response. And then there’ll be a sort of back and forth of letters before we actually end up in the courtroom, which I’m very excited for.

Philip: Tell me about Aurora, because Sweden seems to be, you have Fridays for Future, you have various different other environmental organizations have been started in this country. Is Aurora something that you started yourself with your friends or how did that come into being?

Anton: So I’m also involved with Fridays for Future in Sweden and Aurora actually started as a sort of group of Fridays for Future activists who saw this happening in other countries

and thought, let’s do it in Sweden. And that’s about two years ago. We started chatting to various lawyers, getting a group of law students together, getting more and more activists involved, trying to figure out like, what are we dealing with? How do we start? And then we founded the organization Aurora last summer, like summer 2022, no 2021.

And since then, we’ve been sort of figuring out how to get organized ourselves, get funds in, get legal professionals in and then actually produce lawsuits. And this is notably different from many other court cases or climate cases around Europe, where they’ve often been brought by established organizations.

This is brought by a very grassroots organization that’s very young and founded by youth. So it’s a very different situation financially and organizationally compared to various other cases.

Philip: Sweden has this great reputation from yourselves, Fridays for Future, Greta Thunberg, the Axelson sisters are involved there as well – they’re always great to get on camera, they speak better English than I do – (but) why do Swedish teenagers, Swedish young people feel this so strongly to the extent that they’re prepared to act as much as they do? They’re prepared to take their own government to court over it.

Anton: Yeah, I think Sweden is, we feel a major frustration with Swedish policy because Sweden is touted and lauded as being such a climate leader and talked about as leading the green transition and being world leading on climate and environmental issues. And once you start like actually examining this, it’s all a facade. It’s all based on creative accounting, loopholes and greenwashing basically. So I think there is a major frustration among Swedish youth that this is the awareness of this is so low.

So I think that’s one of the things that really drives me, the sort of massive disconnect between what’s actually going on in Sweden and what people think is going on in Sweden. But we can also see that this is a global movement of youth who are, there’s a similar case being brought in Norway now also by youth. Youth have been involved in the climate cases in Germany. And there’s a case from Portugal where six Portuguese young people are suing basically all of Europe. They’re suing the entire EU and other six states for lack of climate action. So it’s not concentrated in Sweden. It is a global movement of youths using every tool at their disposal in order to get climate action basically. It’s a big change really.

Philip: It’s always struck me that when the international media comes to me and they say, okay, there’s a climate protest going on. These young people in Sweden are protesting and there might be 10, 15, 20,000 people walking to Medborgarplatsen or something right down there by the parliament house. And I often wondered if the government just weathers the storm?

You go out there, you march, you bring your loud hailer, you bring your banners, and then we all go home and nothing changes. What response have you had from politicians that you’ve spoken to, from academics that you’ve spoken to? Because it strikes me that they’re kind of just waiting for all this to pass, that they expect that they’ll just continue on as normal if they just say nothing and do nothing. Do you get the same impression or do you feel that on some levels of government that there is a willingness and a desire for change?

Anton: It’s an interesting question because in my experience, talking to politicians is a bit like talking to a brick wall. They’ll invite you because they want to have a discussion and they want to mostly talk about how they’ve had a discussion with young climate activists.

And then you’ll talk and you’ll bring up all your issues and then they’ll ignore everything you say and try to talk to you and explain to you that they’re actually doing something. And I definitely feel heard in what you say that they’re just waiting for this to pass.

They’re waiting and in large, like cynically it has in many ways, like the climate movement in Sweden in 2019 was massive. We had 50,000 marching on the 27th of September and then the pandemic hit and the momentum died and the media just hasn’t picked up again and the momentum hasn’t picked up again.

And now we’re getting under 10,000, like every time we try to mobilize for a big demonstration. And that’s one of the reasons I think that it’s so important to do new things, to try new things and use all the tools at our disposal. And like suing the Swedish government is the new tool.

It’s doing something new and showing that we’re not going anywhere. We’re in this for the long run. This is a long-run project. It’ll take several years for this to finish, presumably. And I think it’s important to show that we are still here. We are still fighting.

We still care about this and the situation is just getting worse. And therefore we can’t afford to stop.

Philip: It’s almost become, there’s many friends of mine, many Irish people who talk about the brand of Sweden. You know, you mentioned it yourself there that, you know, they’ve greenwashed themselves. Oh, you know, they’re at the cutting edge of environmental technologies and all that, when in fact the numbers are going in the wrong direction. Have we made a mistake in having so much focus on one person in Greta Thunberg, who despite

the fact that her wonderful dog Roxy is from Cork and so she has her Irish connection as well, is that a mistake on the behalf of the media, on behalf of journalists, that, you know, we sort of invest her with all this meaning and then we just ignore everything else that happens? What she says is important for 15 minutes and we kind of ignore everybody else.

What would you like to see, how would you like to see journalists approach the climate crisis in Sweden and around Europe in the way we cover it?

Anton: Well, you’re absolutely right that there becomes a massive individual focus. You focus on Greta or other individuals. And when it’s other people in other countries, they’re often referred to as the German Greta Thunberg or the French Greta Thunberg. And it just shows that we can’t really, the media is choosing not to sort of talk about the movements. They’re not talking about the sort of collective people’s movements demanding change and they need to talk about one person.

And then, like you say, they listen to that message and then it disappears. And like her message from the start has been, don’t listen to me, listen to the experts, listen to the people who are suffering the consequences of the climate crisis already. Talk to the people in the global south who are having their communities destroyed, their lives taken away and their families dying, et cetera. Talk to those people, talk to the climate scientists who know what’s going on. Don’t listen to me. And the media keep giving her the platform and they keep inviting her to say the same things over and over and over again without like actually changing the way they report about the crisis.

Because there’s no reporting of the climate crisis as if it was a crisis. It’s reported as yet another issue. It’s not talked about as an existential crisis. And if it was, it would dominate all news media all over the place. It would dominate every business meeting, every conversation, just like COVID did.

Philip: When the pandemic hit, we realized we were in a crisis and we talked about it that way. With the climate crisis, we’re not. We could have just ignored. We tip away and we keep going on. We go, ah yeah, somebody will sort that out eventually.

Anton: Exactly. It’s too big and we don’t take it in.

Philip: If we look at your own upbringing here, I mean, for us, it’s kind of amazing to stand back and see Anton Foley, you know, with his connection to Ireland, taking this case. Where does your connection to Ireland come from? Where does your accent come from?

Anton: So my dad’s Irish and he grew up in Tipperary. And when I was 10, I lived in Dublin for a year. So our family moved there. My mom’s Swedish and they met in London when they were both studying there. I was born in Sweden and I’ve lived my whole life in Sweden, aside from the one year I lived in Dublin. And then I have a lot of family. My grandparents are in Tipperary and the rest of my family in Dublin. So I’ve got a lot of contact with them and really.

Philip: Is it something that’s very close to your heart kind of thing?

Anton: Yeah, absolutely. I feel Irish as much as I feel Swedish, sort of very much.

Philip: I think often a lot of people, they’re like, you’re half Swedish, half Irish. And it’s like, no, I’m Irish and I’m Swedish. There’s no half.

Anton: Yeah, you usually refer to it as being both Swedish and Irish rather than half of nothing.

Philip: Have you had any contact with or any interest from Ireland? Have you had contact with Irish environmental activists, for instance? Have you been there to speak about the case that you’re taking?

Anton: No, not in relation to Aurora. I know a number of people because Fairness for the Future is such a global and international movement. I know several environmental and climate activists in Ireland. And I actually had contact with some researchers as well and lawyers who are Irish, but not haven’t been there since the case was launched.

Philip: If we look back to the last election, which took place in September of last year, now it’s amazing, it seems like an awful long time ago. We got, I wouldn’t call it a centre-right government, we got an extremely right-wing government there. Miljöpartiet, the Green Party here in Sweden, was roundly abused and left, right and centre, online, offline, on the news, etc. etc. Why does environmental politics get such a hard time in a country which the rest of Europe sort of looks to as a bit of a beacon on that front? Why is the domestic political discourse around green politics and around environmentalism so tough, do you think?

Anton: Because people feel threatened. People feel threatened by people telling it how it is. We go out there and we say, yeah, we’re in an existential crisis, we need to adapt. Everything’s been doing wrong so far. And right now we need to change every aspect of our society. And when we’re saying that, we’re not making it up, we’re quoting the IPCC, like a conservative scientific body by the UN who produced incredible assessments of climate science. They say we need fundamental and far-reaching changes in all aspects of society.

And we go out there and people feel threatened. And they feel scared and they don’t want to take in it, so they deny it. And then they abuse the people who try to say this. And it’s a massive issue that people who are, because it discourages people and it scares people off telling it how it is, because there is so much, so much abuse.

Philip: One of the expressions that you hear a lot when Greta is down there on a Friday morning or when there’s a rally or when Aurora are taking cases like this, is the expression climate justice. A lot of people my age and older maybe hear that and we don’t actually know what it means. What does climate justice mean to you? What do you want to see in the way of climate justice?

Anton: Well climate justice is all about understanding the intersection between climate change and the climate crisis and ecological collapse and other aspects of social justice.

So gender equality, racial equality, class justice, all of these things. Global justice between the global north and the global south. This is very concrete. We see that the climate crisis has been created by not humanity as a whole, but by a very small portion of humanity. It’s being created by mostly rich people in the global north. That means Europeans, that means North Americans, that means Japan and South Korea and Australia. And this is one of the things that I think people feel threatened by because they realize that we are responsible for the disasters that are killing millions around the world.

And despite the global north and rich people being the sort of people with the highest carbon footprints, the people who are causing this disaster, they’re not the people affected by it. Africa is the most climate-vulnerable continent and is only responsible for 3% of cumulative carbon emissions. While the US and Europe are responsible for most of the emissions and we’re not being hit, we are adapting. The impacts we are seeing in Europe and the US we can adapt to. Like almost 99% of climate related deaths occur in the global south and those countries are not responsible for the crisis.

So it’s about realizing that the most affected are the people who are least responsible, which means that we as global north countries and rich countries have a responsibility to lead this transition and to lead the transition to a clean green economy.

And we can see that in our case, we’re centering climate justice in the case. And this has always been at the center of international climate frameworks that rich countries need to lead the way. This means that Sweden has a disproportionately large share of emissions reductions.

We have a big responsibility because we have high emissions historically and because we’re a rich country with a large capacity to make the transition. So this means that Sweden needs to reach zero emissions way before countries such as sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia or Latin America, etc. So that’s that justice aspect is at the center of our case, meaning that Sweden needs to reach zero emissions way before it would otherwise.

Philip: A lot of people will listen to what you’re saying there and they will think that I like

my life at the moment. I like my diesel car. I like my skiing holiday. I like to go to Thailand at Christmas and to get away from the snow and that kind of thing. What has to change? Do people will say to you, oh, you know, they want us all to become vegan and to wear sort of hemp shorts and that kind of thing? What kind of things have to change just to avert the crisis, let alone sort of reverse it?

Anton: I think it’s all about education. I think we have a good word in Swedish called folkbildning, which is sort of broad, voluntary public education for everybody.

And I think if people realized what kind of shit we’re in, then there wouldn’t be that attitude. Like, there wouldn’t be that resistance, the resistance because people care about other people.

I believe that people like care about their friends, their families, and even people they don’t know. People are genuinely sort of empathetic creatures. And like, I believe that if people realize that the way we’re living our lives is leading to not exaggeration, millions dying every year in other parts of the world. If people actually understood that on a fundamental level and understood that this is only going to get worse, and that soon we might reach points of no return where the climate crisis becomes starts and like feedback hits feedback loops, that means the warming enforces itself. I think if people understood that on a fundamental level, then that would change.

I also think there’s like a mindset that we’ve been taught to think in a certain way. We’ve been sort of imprinted with a sort of consumerist thought, that we’ll be happier if we just get that extra large car, if we get that expensive watch or if we can buy more clothes.

But there’s like all studies show that after a certain point, buying more stuff doesn’t make us happier. We sort of think it does, because we need to aspire to sort of have as much stuff as the people who are one step above us in the sort of societal hierarchy.

They have private jets, they have mega yachts, therefore we need to move in that direction as well. But there’s nothing showing that that actually makes us happier. What actually makes us happier is sort of it’s community, it’s doing stuff with our friends, it’s having strong bonds with our family, it’s access to nature, all of this stuff, sports and culture and art, music, all of this stuff is what actually gives happiness if you listen to sort of empirical research on this. If we created societies that could centre this instead of consistently having to buy more and more and more stuff every year, then we’d have not only a healthier planet and healthier ecosystems, we’d also have happier people. And that’s been shown that communities that live more in tune with nature are happier.

Philip: It’s interesting what you say because when you look at how Sweden celebrates midsummer for instance, there’s that aspect of quite simple food, often preserved so that you’re making the most of the previous harvest etc. Go swim in a lake, that’s free still as far as I know. That all these things are very simple pleasures and that they are very much at the heart of Swedish culture. Is this consumerism, now you’re a lot younger than me so maybe I should be the one asking this question, is this consumerism a new thing in Sweden do you think? Have we abandoned that sort of Olof Palme’s people’s home that he talked about through the 70s and the 80s and adopted this sort of consumerism on steroids that the rest of the world seems to be such a big fan of?

Anton: Yeah, there’s been a massive change in attitudes to this in Sweden since the late 80s and the 90s and we’ve been sort of hit by the global sort of neoliberal wave of Milton Friedman and Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and people like that. And that sort of came to Sweden in the 90s and we sort of changed the way we approached our society and we started restructuring that. And I think that definitely involved that the consumerist sort of approach got even stronger in Sweden but it’s existed for longer than that.

And it’s, I really like what you’re saying about Midsommar, I love Midsommar. I think it’s a lovely tradition and I’ve always really enjoyed it and, like you said, it’s sort of very simple things. But by the way we measure progress in our society which is largely by GDP and GDP growth, none of the activities you said contribute to that – buying a larger car will contribute to that but it won’t make me happy the same way that swimming in the lake with my family and eating herring, I don’t eat herring – I don’t like herring, but eating herring on Midsommar will.

Like that’s what makes us genuinely happy, but that’s not included in the sort of metrics we use to measure progress and to measure how healthy society is. And if we want to get anywhere about this we need to reframe that and we need to reframe what matters.

Philip: A lot of the opposition, when this podcast comes out for instance, as soon as it goes out on Instagram there’s going to be comments under it about, there’s a couple of ways of

looking at it. One is that this is like a Trojan horse for some form of communism, this is some sort of pie in the sky aspirational, ”yay! let’s all be in this together!”, Stalinism kind of thing you know? There is undeniably a certain left wing tint to it but is that a fair reflection of what young people in the climate justice movement want, that they want a more egalitarian society on every level?

Anton: I want a more egalitarian society and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I do however think it’s very interesting that as soon as you start talking about, yeah maybe we shouldn’t like commit collective suicide and set fire to the world, that the immediate response as soon as you say that is calling you a communist – that says a lot, I think.

But yes, I absolutely want a more egalitarian society and I think we need to live, I think we as people would be happier, everybody would be happier if we lived in a sense where we

could actually satisfy everybody’s needs and that’s also a large part of what climate justice is about – how do we meet everybody’s needs while living within planetary boundaries? And all studies show that it’s very possible, it’s very possible. We just need to stop the vast overconsumption that we’re going on with like 50% of carbon emissions are emitted by the richest 10% in the world, and if the richest 10% in the world lowered their carbon emissions to the average European – which is still significantly too high – like, a third of all global greenhouse gas emissions would be erased. That’s a massive reduction just from like the richest going down to what is already a very like superfluous lifestyle. So I think we need to understand that we can lift billions out of poverty, we can make sure everybody has access to clean water, education, housing, free healthcare, all of this stuff, food security, energy security. We can achieve all this within planetary boundaries.

We just can’t do it while also flying private jets all over the world and we’re sort of at a precipice where the vast inequalities that dominate our world have come to a point where we’re facing ecological collapse and we either need to decide do we keep going,

do we keep running towards the abyss? And in the end that will come back to haunt us as well – who are the perpetrators, or do we actually reshape society in a way that actually is

built for people? I suppose the term is people not profit, it’s putting people at the centre of these things rather than chasing money.

Philip: Speaking of money, the second comment under the Instagram picture they’re going to put out with this episode is going to be that you’re all bought, that George Soros is paying

you all, every single young activist out there, that you’re, I’ve heard the word puppets used so many times. How much does Soros pay you every month Anton?

Anton: I wish.

Philip: By the way, if George Soros wants to go to patreon.com/ourmaninstockholm, he can continue to support this podcast, but on a serious note, who does support you? Is this just people around the country who share your view of this thing?

Anton: Like this lawsuit is mostly publicly funded, like we have an open crowdfunder, it’s on chuff.org, it’s links on our website and in our social media and when we handed in our

lawsuit and we got massive media attention we pulled in like 40-50 thousand euros in a very short amount of time in a day or two from this being exposed and we’ve raised almost a hundred thousand euros just from that crowdfunding.

So we have received a massive public support for this. We have no billionaire funders as of yet and it’s also very telling that the same sort of, the same people who are attacking the climate activists are the people who will peddle the anti-semitic conspiracy theorists, conspiracy theories about Illuminati and Jewish billionaires etc.

Philip: One of the things that has been a major topic of discussion this winter has been the cost of energy and when you look a little bit closer at it you’ll find that there’s no shortage of energy in Sweden. In fact Sweden has never produced more electricity than it’s doing at the moment despite Ringhaus 1 and 2 being out of action and it’s actually the market and how the prices are set in the market that’s the problem. How does the climate justice movement or the people in Aurora for instance, how do you view nuclear power? Because a lot of people look at it and they go, oh makes sense, you build that, yeah loads of electricity, free electricity for everybody. Like the way you use geothermals in Iceland. Is that something that you look at, you as a movement look at and go that’s a great idea

or is it a bad idea?

Anton: I think the main thing to talk about when it comes to nuclear energy and the climate debate is to understand that we’re in a culture war around nuclear energy and that it’s been allowed to hijack the entire climate debate in the sense that we’re not talking about the

issues. We’re not talking about our largest polluting industry, which is the Swedish forestry industry. We’re not talking about over-consumption. We’re not talking about how our society is structured in a way to prioritize the wrong things and instead we’ve been caught up in a war over nuclear power or no nuclear power and the answer is – who cares, honestly?

To get more technical, Vattenfall, our state energy company say that we can have nuclear power up and running in Sweden in 15 years maybe. 2035, I guess that’s 12 years nowadays.

And like if you look at our carbon budgets, we just don’t have time to wait for 12 years to have sort of new electricity come online to replace fossil fuels to electrify the industry or whatever. We need to cut emissions tomorrow and like Sweden should be on zero emissions significantly before we can have any nuclear power come online.

So if anybody’s talking about nuclear power as a climate solution, they just don’t understand the urgency of the situation. I think it’s also telling that we can’t really focus on what matters. Like when we talk about energy and cutting energy prices, we don’t talk about the fact that the Swedish forestry industry and the paper industry use like a quarter of Swedish energy and they don’t have to pay any electricity tax because that’s a massive state subvention.

And we don’t talk about how the state subsidizes, and we don’t talk about how the state subsidizes Bitcoin mining like holes, server holes. And those, they’re using massive amounts of electricity and at the same time people, mostly in the south of Sweden, they can’t pay their energy bills because they’re so high and the energy prices are so high.

So we’re just caught up in a situation where we refuse to look at the root of the problem. We’re not producing too little energy. We’re honestly producing too much energy and we need to like scale down destructive industries if we’re going to get out of this mess. That does include Bitcoin mining and it does include clear-cutting forests.

If we scale that down, we would have massive reductions in electricity usage and falling prices as a result. And that’s even without talking about the structural market reforms that you were talking about, how we import electricity prices from fossil gas dependent Germany and Poland, et cetera. And that’s what sets the prices for so-called clean energy coming out of Sweden.

Philip: If you look at Miljöpartiet, the Green Party in Sweden, and this goes for Ireland and it

goes for Germany as well. I remember when they first started to rear their head in electoral politics in the mid-1980s, I think it is a great idea – I have been tremendously disappointed by most of those movements because they’ve been a third wheel for centre-right and right-wing governments pretty much throughout Europe. Is it a mistake to focus on the environmental aspect? Because earlier on we spoke about climate justice, how social justice and climate justice go hand in hand. Is the time for that kind of party past? Is it time for a new political movement or can you still find something in Miljöpartiet, in the Green movement that can actually be useful in terms of electoral politics?

Anton: Well I think it’s important to separate the environmental movement in general and the party-political wing of the environmental movement, which has largely deviated. That’s true in Sweden from Miljöpartiet. It’s definitely true in Ireland for Eamon Ryan and the Greens. We see in both of our countries how the Greens, they’re not green. They’re not talking about any structural reforms. They’re not talking about any urgency. They’re not talking about drastically cutting emissions.

The Swedish Greens are still buying the myth that our forestry industry is sustainable and that we can reduce our emissions by clear-cutting all of our forests and burning them for energy. And there’s no crisis realisation. The crisis realisation is completely absent from all parties.

And that’s another thing that’s so striking when you realise how bad everything is, that there is no political party that’s proposing anything even close to what we need. There’s no political party that’s peddling demands to treat the crisis like a crisis. And when you’re in that situation, what do you do?

If you’re told that the way to effect change in your democracy is to join a political party and campaign and get into Parliament and become a politician, when there’s no party that’s doing what they’re supposed to do, what do you do?

You don’t have time to start a new party and wait for that to get public support. What’s needed is broad public movements, people standing up where they are and saying, we’ve had enough. That’s the only thing that’s ever led to fundamental change in society.

That’s how we’ve won gay rights and women’s rights. And that’s how workers won the right to vote and the right to shorter working weeks. All of this comes from popular movements. It comes from unions. It comes from strikes. It comes from people standing up for what they believe, coming together and bringing collective action, and the Green parties across Europe don’t represent any of that.

The Greens in Germany are now supporting the coal mine expansion in Litzerath and called the police brutality involved in clearing all of the activists out there ”necessary”. All of this stuff, there’s no connection to the people. There’s no connection to the people’s movements. And often we’re associated with Miljöpartiet because people just assume, they bunch them all in together – everybody who cares about the environment into the same sort of basket.

There’s obviously people who are really good people and wanting to do the right thing and saying the right things, even within these institutions. But we can’t forget that the institutions are the problem. The way we structure our society is the problem and that change is just not going to come from inside. It needs to come from the grassroots level outside putting pressure.

So that’s why I’m not engaged in any political party and why I would encourage everybody to join a movement like Friday for Future way ahead of joining a political party if you want to make real change for the climate.

Philip: When you hang out with people of your own age in Friday for Future, when you discuss the legal case with Aurora, what’s the atmosphere like? Are you hopeful? Are you angry? Are you fucking ready to give up at this point?

Anton: I mean, it’s honestly a bit of all of it. Like, I’m not going to lie – obviously there’s despair. Like you can’t not be. If you read what’s going on and you truly understand there’s no denying that there is a level of despair, a level of ”it doesn’t matter”. But in the end, we are hopeful, not from any change that’s coming from any governments, not from any of the sort of green transition that’s being talked about that’s already going on, but from the movements like ourselves, the movements that inspire us, the people that sort of are standing up for what they believe in, who are trying to affect that change where they stand.

It’s inspiring to see indigenous peoples around the world who have been defending their lands and protecting their biodiversity for centuries, despite a complete onslaught and attempt to for as well genocide as ecocide.

And it’s inspiring and it’s inspiring to see how people have continued fighting and how people continue to fight today. And I see sort of historic revolutions. I see how anti-colonial movements in Africa and the Middle East and Latin America have sort of achieved democracy. I see how women’s movements across the world have won massive strides to get to feminism. I see how all of these things have happened and it’s hard to believe that it can’t happen again. At the same time, the movement is way too small and we don’t have time.

Like, the carbon budget for exceeding the 1.5 degree limit is exceeded in 2029 with today’s emissions, which are rising. So there’s not a lot of time to wait. At the same time, we need to believe, I need to believe, otherwise I couldn’t go on.

This dominates most aspects of my life at the moment because it’s hard to think about anything else – once you get that emotional realization of what’s going on and what’s going to happen, it’s difficult not to, it’s difficult to dedicate your life to anything else.

Philip: What’s the most effective thing in terms of convincing people like me, people like your mom and dad, that little bit older, that you’re actually right, that this is a crisis and that we’ve got to do something about this now. What do you find most effective? Because sometimes when we talk about things like, especially in this city, when we talk

in Stockholm about integration and we talk about racism and we point the finger at people and people get very, very defensive. And I’m thinking that maybe the same thing happens when we talk about the climate crisis, that people become very defensive. Can we put an arm around people’s shoulders and try to lead them into this way of thinking

that you have? Or do you just have to grab them by the ear and pull them with you?

Anton: I think it’s a mix. Like on one hand you need to be like, yeah, studies show that if Sweden’s emissions were to be in line with our fair share of the 1.5 degree target, we would need to be cutting emissions by about 40% a year starting this year. That’s practically impossible. And it’s insane that that isn’t enough to get people to react. Partly people think we have it under control because everything they hear from politicians, from media, from companies, from everybody, it’s we have things under control.

Things are going in the right direction. They’re going a bit too slowly and we need to ramp it up, but they’re going in the right direction. And even Miljöpartiet have that rhetoric, like it’s going too slowly in the right direction.

It’s not – it’s going in the wrong direction. And once people realize that, I think there’s a difference. The other thing though, I think that you need to, and this is where I think climate justice is so powerful as a term and as a sort of framework for understanding the world. When we realize that the same type of policy and the same type of change that is needed and urgently needed to avert the climate crisis and avert the worst consequences of the climate crisis, that same change is what will improve people’s lives. That same change is what will like lift people out of poverty, fight gender inequality, fight racism, all of this stuff. It goes hand in hand.

If we fight the rampant consumerism that dominates our society, we won’t be forced to work as much as we do today. We won’t be forcing people in the global South to sort of work slave labor in order to produce more clothes for us. Once we realize that our liberation is tied together, we can collectively work towards the same goal. I think that gets to a lot of people.

When you show studies that say that, for example, shortening the working week, the effect that would have on our greenhouse gas emissions is massive, as well as giving us more time to do what we love and spend time with the people we love, and we see that the public support for policies like that is massive – it’s absolutely massive.

And yet we have one and a half political parties representing maybe 10% of the population that are actually actively ruining that demand. And there’s nothing clearer for me that change needs to come from below because it will never come from inside the institutions that are the problem here. And I think everybody has a bit of fight in them – everybody has a bit of resistance. And right now, powerful forces are trying to paint certain groups as

scapegoats and direct that anger at the system.

Like all of the anger that’s leading to the rise of far-right nationalism and racist movements in Sweden comes from austerity, just like it did in Germany in the 30s. People were poor. You had the Great Depression, you had hyperinflation, and then someone comes along and says that, yeah, this is all the fault of one particular group of people, and people believe that. And the same thing is happening again today.

But if you direct that rage at where it should actually be directed, it’s not the immigrants’ fault. It’s the fault of a global economic and political system that forces people to

live like this.

And once people start realizing that, then I think it becomes a lot easier. And a lot of the time, people say that we’re losing focus on the climate issues when we talk about gender inequality, when we talk about racism, when we talk about all of this stuff. But I think it’s a strength, talking about all of this, because I think that’s how you reach people.

And you say that the climate movements, you show solidarity between movements. My favorite movie is the film called Pride, which is a really, really beautiful story of solidarity between the gay rights movement in London in the 80s and the Welsh coal miners – it’s a bit ironic that it’s coal miners, in this case – but the coal miners strike in the 80s.

And this is under Thatcher. And it’s a lovely show of two-way solidarity, how both the gay rights movement and the workers’ rights movement got stronger by them supporting each other. And that’s how I think we will do it today, the climate movement and the feminist movement and the workers’ rights movement, if we all unite and understand that our interests are the same.

If we can show that solidarity instead of hating each other, I think then we can

get to a really powerful place.

Philip: What’s the process now for the court case? You mentioned that you’re expecting some sort of response from the government. You’ll get a decision from the court whether or not they’re prepared to hear your case. When do you expect this to happen? Is this how long is a piece of string territory or what?

Anton: No, so like the response from the court should come in within a few weeks. And that’s very, very nervous, obviously, knowing if they’ll sort of hear the case or not. It would be very sad and a bit embarrassing if they decided it wasn’t worth hearing.

In that case, we can always appeal, but that should come within a few weeks. And then after that, the state gets to respond and then back and forth. And then maybe we’ll be in court like actual physical court hearing dates this autumn and maybe early September, I’d say. But it’s hard to know exactly.

Philip: What happens if you win?

Anton: Our claim and what we mean is that the state has the responsibility to reduce its emissions in line with its fair share in order to limit global temperature rise to one and a half

degrees over pre-industrial levels. A lot of technical words, but it basically means we need to follow a really, really strict emissions reductions curve. And aside from reducing our emissions, we also need to restore and protect carbon sinks, so forests and seas and wetlands, et cetera, that take up massive amounts of carbon from the atmosphere.

So once we – if we – win, then the state would be legally obliged to follow this emissions reduction curve. Now, what would actually physically happen is they would not manage to reduce their emissions in line with this, because this means extremely stringent emissions reductions. And in this case, reaching net zero around, in around five years. That’s not really going to be at the very least, like politically possible.

They just won’t do it and they won’t worry about the consequences. In practice, that means you can make the case that like this, this lawsuit would set a legal precedent and that might be the most powerful aspect of it, because it would mean that every court having to take a decision on a planning permission and every court having to take a decision on any case, like of building anything or developing a project would need to take like, would need to take this emissions reductions curve into account.

Philip: So people wanting to like expand fossil fuel infrastructure just wouldn’t be possible because it’s not possible to do under this? It would effectively become against the law.

Anton: Yeah, exactly, pretty much. And that opens up for us and other groups to run sort of court cases that mean that would forbid something you can forbid, like fossil fuel extraction or clear-cutting forest or all of these things that would be blankly against this emissions reductions curve. So the legal precedent it would set would be absolutely massive.

It would completely redefine what’s possible and not possible to do in Sweden. And I get that that’s really terrifying for some people, but I think we need to get past the point where we’re more scared of the sort of shift to a better society than we are of the climate crisis, because the climate crisis is significantly scarier.

Philip: And if you lose, where do you go from there?

Anton: There’s obviously three levels of court. So whoever loses in the first instance in the district court will almost certainly appeal and the same in the regional court. So possibly this will end up in the Supreme Court, maybe even probably. And if we lose in the Supreme Court, there’s the possibility of taking it to the European Court for Human Rights.

And if we lose in all these instances, then we will be liable to pay opposition legal fees. Presumably that also depends on what the court says and what the state asks for. But we have plans to want to run other types of sort of environmental legal activism.

So as a group, we will probably run other lawsuits. There’s a lot of ways to advance this struggle in the courtroom.

Philip: Do keep us informed.

Anton: Thanks so much for talking to me.